The Ouija Board Is Creepy Alright, But Not For the Reasons You Think

Ever fallen down the on-demand TV hole and realized you just spent four hours wasting your life away watching paranormal investigator Zak Bagans and team freaking their way out of dark rooms?

A recent episode of Ghost Adventures—dubbed The Samaritan Cult House—showed the team using a Ouija board allegedly taken over by a “demonic” force. Start at the 29:02 mark of the clip below for a peek.

If you watch through the rest of that episode, you’ll notice Ghost Adventures cast member Jay Wasley becomes so agitated by what the board spells out that he leaves the room, himself and fellow ghost hunter Bagans claiming a demon was taunting him with accurate information Wasley had told no one.

But these revelations aren’t occuring on their own. After all, Wasley was touching the “spirit” board’s planchette.

And so the believer vs. skeptic debate ensues.

Is a malevolent entity terrorizing Wasley by reading his mind? Are Wasley and team deceiving the audience to create drama to ensure the show keeps its ratings up? Or is Wasley simply revealing what’s on his mind by either consciously or unconsciously moving the planchette on a board whose layout he’s been intimately familiar with since at least his early twenties?

Read Also: The Trick to Getting on Your Second Brain’s Good Side

And: Listen to Your Heart to Read Minds? Science Closer to Saying Yes

“The idea that one’s own unconscious is moving the Ouija board planchette is not a new one.”

(Left photo: Flickr user Vito Fun (CC BY 2.0). Right photo: Flickr user Indi Samarajiva (CC BY 2.0). Headliner photo of a Ouija board close at the top of the article up by Flickr user Gabriel Molina (CC BY 2.0)).

The Concept of Ideomotor Actions

Ideomotor response is commonly seen in hypnotic sessions, a behavioral and/or physiological reaction you don’t even realize you’re making in response to hypnotic suggestions. A person’s mouth salivating moments after they’ve been told under hypnosis that they just bit into a lemon? That’s an ideomotor response. You don’t notice you’re doing it. But you are.

And ideomotor actions go beyond hypnosis.

Surgeons claiming patients under general anesthetic could hear them talk during surgery and physically respond to surgeon requests as if subconsciously aware is another example of ideomotor action [1]. Once woken, patients had no recollection of being aware of their own surgery.

A comparably controversial example is facilitated communication, a technique designed to help patients with severe autism, cerebral palsy, and other conditions severely hindering movement and communication express themselves. With facilitated communication, a facilitator holds a patient’s hand down on a board featuring letters of the alphabet. In theory, the patient guides the facilitator to letters on the board to spell out words. Though supported by some as a valid technique, facilitated communication was discredited by the scientific community after multiple studies showed that the thoughts being spelled out were actually those of the facilitator and not the patient [2]. Yet if taken at their word, facilitators truly believed it was the patient guiding their movements. It didn’t dawn on them that they might have been the mastermind behind the message all along.

The Original Function of the Ouija Board

The idea that one’s own unconscious is moving the Ouija board planchette is not a new one. Berlin resident Adolphus Theodore Wagner first released his psychograph for that very reason.

The psychograph was a “talking board” patented by Wagner in London circa 1854, 37 years before its remarkably similar American counterpart, the Ouija board, was put on the market [3]. Also called a “thought indicator,” Wagner, a music professor by trade, wanted to help people access their full creative potential by having them discover their subconscious thoughts through his invention [4]:

“A colleague of the inventor, Freiherr von Forstner, reports that several such devices were sold in California, and to advertise the sale, Forstner published no fewer than four psychographically induced poems; these were attributed to supposedly inartistic and not especially literate Prussian citizens (a first lieutenant in the Prussian Army, and a 12-year-old girl). While hardly a challenge to the literary elite, psychographically induced literature offered the promise of socializing genial invention. Indeed, the appeal of the psychograph for early commentators rested partly on the assumption that anyone could tap into their “genius” to some extent.” -excerpt from David Trippett’s 2013 book Wagner’s Melodies: Aesthetics and Materialism in German Musical Identity

“The psychograph was a “talking board” patented by Wagner in London circa 1854, 37 years before its remarkably similar American counterpart, the Ouija board was put on the market. Also called a “thought indicator,” Wagner, a music professor by trade, wanted to help people access their full creative potential by having them discover their subconscious thoughts through his invention.”

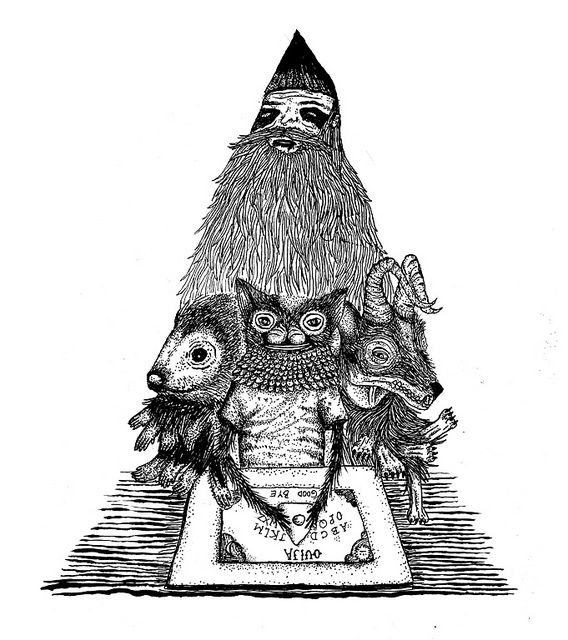

(Drawing by Flickr user Blopa (CC BY-ND 2.0).

That Wagner’s board found its purpose shift from discovering one’s unconscious thoughts to communicating with the dead, repackaged and commercialized into an American parlor game by end of the 19th century, isn’t so surprising given Europe’s longstanding obsession with and the New World’s rising interest in spiritualism. It was a time before the miracles of modern medicine made reaching old age a standard reality, when life expectancy was ravaged by war, maternal death by childbirth, and uncomfortably high child mortality rates. The chance to speak with deceased loved ones gone too soon proved irresistible and widespread, a popular and socially acceptable activity at the time which, in many ways, still is today.

So who is doing the talking, exactly? Ethereal spirits guiding human hands on the planchette? Or mere mortals unaware of their own movements? Skeptics have been insisting for over a century that Ouija board answers are ideomotor actions, participants’ own either deliberately deceptive or innocently unconscious movements. One Canadian team decided to test that hypothesis with a robust experimental design replicated across two separate studies producing results so unexpected and “so dramatic we couldn’t believe it.” [5]

The Ouija Robot

Researchers from the psychology, computer science, and electrical and computer engineering departments of University of British Columbia teamed up to test the ubiquitous spirit board [6].

First, researchers Hélène Gauchou, Ron Rensink, and Sidney Fels recruited student participants with no or next-to-no Ouija board experience to answer a series of yes-or-no general knowledge questions on a computer, questions like “Were the 2000 Summer Olympics held in Sydney?” or “Is Buenos Aires the capital of Brazil?”

Then they paired student participants with a second participant (who was actually in cahoots with the research team) to use the Ouija board to answer more trivia questions. Students were told the second participants were touching the planchette along with them but in another room via teleconferencing with the help of a robot standing in. What researchers didn’t tell students was that the robot was actually mimicking and amplying their own movements, not those of the red herring “second participant” designed to throw students off. And of course, students were instructed NOT to move the planchette. Then they were asked those general knowledge questions. Roughly half of the questions were brand new, and the other half were questions the students had already answered on the computer.

In a slightly different design, students were blindfolded and paired up with another “participant” to answer questions. No robot this time though. But again, the blindfolded students were the only ones who could have possibly influenced the board because the second “participants” removed their blindfolds and hands off the planchette as soon as students were properly blindfolded themselves. Students had no idea their hands were the only ones on the board.

The hilarious part? Some students complained that their fellow participants were moving the planchette. All students swore they were only following the movement. And all of them expressed surprise when it was revealed that they were the only ones who could have possibly budged the planchette.

But here’s where things get really interesting.

Into The Depths of Your Hidden Mind

Those trivia questions students answered before and during the Ouija sessions? After responding to each one, they were asked if they were confident of their answer or if it was a simple guess.

In the regular non-Ouija Q&A session on the computer, for answers students claimed were pure guesses, they guessed right about 50% of the time, almost the same as chance. That’s to be expected.

But during the Ouija sessions when they thought their ghost participant was moving the plank to answer questions? They guessed right 65% of the time on questions they claimed to have no idea what the answer could be, well above chance. So much above chance, it stunned the research team.

How could they possibly be guessing more questions right with the Ouija board, when they thought they didn’t know the answer and assumed it was their ghost partner moving the plank?

Did the students’ belief that they weren’t moving on the Ouija board allow them to tune out of their conscious mind and tap into subconscious memories, their unconscious intelligence? Are they, and by extension all of us, more knowledgeable than we realize?

One thing is for sure. These results point uncannily in the direction of the Victorian era psychograph. The “thought indicator” was supposed to reveal the user’s subconscious thoughts and it appears as though its spiritualist usurper, the Ouija board, may have been staying true to Wagner’s patented vision all along.

In a Smithsonian Magazine interview conducted close to a year after the study was published in Consciousness and Cognition, Dr. Rensink said the team were trying crowdfunding to bankroll more Ouija board experiments since “classic funding agencies don’t want to be associated with this, it seems a bit too out there,” he says, a sad state of affairs considering their previous work was volunteer-based and partially funded by Rensink himself to keep it going and yet produced persuasive findings worthy of further investigation, findings that could lead to unblocking the human brain’s “forgotten” memories. Unfortunately, all three have since moved on to other projects.

Of course, it’ll take more than one unusually compelling experiment to convince your average God-fearing exorcist priest that a Hasbro-trademarked board game now mass produced in pink isn’t a portal of demonic chaos and darkness.

But was it enough to convince you?

References

- Cheek DB. The meaning of continued hearing sense under general chemo-anesthesia: A progress report and report of a case. The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 1968; 8(4): 275-280.

- Goldacre B. Bad science: Making contact with a helping hand. The Guardian. December 5, 2009. Online. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2009/dec/05/bad-science-ben-goldacre-column

- Patents for Inventions: Abridgments for specifications. Patent Office: Great Britain 1859: 382-383.

- Trippett D. Wagner’s Melodies: Aesthetics and Materialism in German Musical Identity. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. 2013. Print.

- Rodriguez McRobbie L. The Strange and Mysterious History of the Ouija Board. Smithsonian Magazine. October 28, 2013. Online.

- Gauchou H, Rensink R, Fels S. Expression of nonconscious knowledge via ideomotor actions. Consciousness and Cognition 2012; 21(2): 976-982.

Ever fallen down the on-demand TV hole and realized you just spent four hours wasting your life away watching paranormal investigator Zak Bagans and team freaking their way out of dark rooms?

A recent episode of Ghost Adventures—dubbed The Samaritan Cult House—showed the team using a Ouija board allegedly taken over by a “demonic” force. Start at the 29:02 mark of the clip below for a peek.

If you watch through the rest of that episode, you’ll notice Ghost Adventures cast member Jay Wasley becomes so agitated by what the board spells out that he leaves the room, himself and fellow ghost hunter Bagans claiming a demon was taunting him with accurate information Wasley had told no one.

But these revelations aren’t occuring on their own. After all, Wasley was touching the “spirit” board’s planchette.

And so the believer vs. skeptic debate ensues.

Is a malevolent entity terrorizing Wasley by reading his mind? Are Wasley and team deceiving the audience to create drama to ensure the show keeps its ratings up? Or is Wasley simply revealing what’s on his mind by either consciously or unconsciously moving the planchette on a board whose layout he’s been intimately familiar with since at least his early twenties?

Read Also: The Trick to Getting on Your Second Brain’s Good Side

And: Listen to Your Heart to Read Minds? Science Closer to Saying Yes

(Photo by Flickr user Vito Fun (CC BY 2.0))

The Concept of Ideomotor Actions

Ideomotor response is commonly seen in hypnotic sessions, a behavioral and/or physiological reaction you don’t even realize you’re making in response to hypnotic suggestions. A person’s mouth salivating moments after they’ve been told under hypnosis that they just bit into a lemon? That’s an ideomotor response. You don’t notice you’re doing it. But you are.

And ideomotor actions go beyond hypnosis.

Surgeons claiming patients under general anesthetic could hear them talk during surgery and physically respond to surgeon requests as if subconsciously aware is another example of ideomotor action [1]. Once woken, patients had no recollection of being aware of their own surgery.

A comparably controversial example is facilitated communication, a technique designed to help patients with severe autism, cerebral palsy, and other conditions severely hindering movement and communication express themselves. With facilitated communication, a facilitator holds a patient’s hand down on a board featuring letters of the alphabet. In theory, the patient guides the facilitator to letters on the board to spell out words. Though supported by some as a valid technique, facilitated communication was discredited by the scientific community after multiple studies showed that the thoughts being spelled out were actually those of the facilitator and not the patient [2]. Yet if taken at their word, facilitators truly believed it was the patient guiding their movements. It didn’t dawn on them that they might have been the mastermind behind the message all along.

(Drawing by Flickr user blopa (CC BY-ND 2.0))

“The psychograph was a “talking board” patented by Wagner in London circa 1854, 37 years before its remarkably similar American counterpart, the Ouija board was put on the market. Also called a “thought indicator,” Wagner, a music professor by trade, wanted to help people access their full creative potential by having them discover subconscious thoughts through his invention.”

The Original Function of the Ouija Board

The idea that one’s own unconscious is moving the Ouija board planchette is not a new one. Berlin resident Adolphus Theodore Wagner first released his psychograph for that very reason.

The psychograph was a “talking board” patented by Wagner in London circa 1854, 37 years before its remarkably similar American counterpart, the Ouija board, was put on the market [3]. Also called a “thought indicator,” Wagner, a music professor by trade, wanted to help people access their full creative potential by having them discover their subconscious thoughts through his invention [4]:

“A colleague of the inventor, Freiherr von Forstner, reports that several such devices were sold in California, and to advertise the sale, Forstner published no fewer than four psychographically induced poems; these were attributed to supposedly inartistic and not especially literate Prussian citizens (a first lieutenant in the Prussian Army, and a 12-year-old girl). While hardly a challenge to the literary elite, psychographically induced literature offered the promise of socializing genial invention. Indeed, the appeal of the psychograph for early commentators rested partly on the assumption that anyone could tap into their “genius” to some extent.” -excerpt from David Trippett’s 2013 book Wagner’s Melodies: Aesthetics and Materialism in German Musical Identity

That Wagner’s board found its purpose shift from discovering one’s unconscious thoughts to communicating with the dead, repackaged and commercialized into an American parlor game by end of the 19th century, isn’t so surprising given Europe’s longstanding obsession with and the New World’s rising interest in spiritualism. It was a time before the miracles of modern medicine made reaching old age a standard reality, when life expectancy was ravaged by war, maternal death by childbirth, and uncomfortably high child mortality rates. The chance to speak with deceased loved ones gone too soon proved irresistible and widespread, a popular and socially acceptable activity at the time which, in many ways, still is today.

So who is doing the talking, exactly? Ethereal spirits guiding human hands on the planchette? Or mere mortals unaware of their own movements? Skeptics have been insisting for over a century that Ouija board answers are ideomotor actions, participants’ own either deliberately deceptive or innocently unconscious movements. One Canadian team decided to test that hypothesis with a robust experimental design replicated across two separate studies producing results so unexpected and “so dramatic we couldn’t believe it.” [5]

The Ouija Robot

Researchers from the psychology, computer science, and electrical and computer engineering departments of University of British Columbia teamed up to test the ubiquitous spirit board [6].

First, researchers Hélène Gauchou, Ron Rensink, and Sidney Fels recruited student participants with no or next-to-no Ouija board experience to answer a series of yes-or-no general knowledge questions on a computer, questions like “Were the 2000 Summer Olympics held in Sydney?” or “Is Buenos Aires the capital of Brazil?”

(Photo by Flickr user Patrick Emerson (CC BY-ND 2.0))

Then they paired student participants with a second participant (who was actually in cahoots with the research team) to use the Ouija board to answer more trivia questions. Students were told the second participants were touching the planchette along with them but in another room via teleconferencing with the help of a robot standing in. What researchers didn’t tell students was that the robot was actually mimicking and amplying their own movements, not those of the red herring “second participant” designed to throw students off. And of course, students were instructed NOT to move the planchette. Then they were asked those general knowledge questions. Roughly half of the questions were brand new, and the other half were questions the students had already answered on the computer.

In a slightly different design, students were blindfolded and paired up with another “participant” to answer questions. No robot this time though. But again, the blindfolded students were the only ones who could have possibly influenced the board because the “second participants” removed their blindfolds and hands off the planchette as soon as students were properly blindfolded themselves. Students had no idea their hands were the only ones on the board.

The hilarious part? Some students complained that their fellow participants were moving the planchette. All students swore they were only following the movement. And all of them expressed surprise when it was revealed that they were the only ones who could have possibly budged the planchette.

But here’s where things get really interesting.

Into The Depths of Your Hidden Mind

Those trivia questions students answered before and during the Ouija sessions? After responding to each one, they were asked if they were confident of their answer or if it was a simple guess.

In the regular non-Ouija Q&A session on the computer, for answers students claimed were pure guesses, they guessed right about 50% of the time, almost the same as chance. That’s to be expected.

But during the Ouija sessions when they thought their ghost participant was moving the plank to answer questions? They guessed right 65% of the time on questions they claimed to have no idea what the answer could be, well above chance. So much above chance, it stunned the research team.

How could they possibly be guessing more questions right with the Ouija board, when they thought they didn’t know the answer and assumed it was their ghost partner moving the plank?

Did the students’ belief that they weren’t moving on the Ouija board allow them to tune out of their conscious mind and tap into subconscious memories, their unconscious intelligence? Are they, and by extension all of us, more knowledgeable than we realize?

One thing is for sure. These results point uncannily in the direction of the Victorian era psychograph. The “thought indicator” was supposed to reveal the user’s subconscious thoughts and it appears as though its spiritualist usurper, the Ouija board, may have been staying true to Wagner’s patented vision all along.

In a Smithsonian Magazine interview conducted close to a year after the study was published in Consciousness and Cognition, Dr. Rensink said the team were trying crowdfunding to bankroll more Ouija board experiments since “classic funding agencies don’t want to be associated with this, it seems a bit too out there,” he says, a sad state of affairs considering their previous work was volunteer-based and partially funded by Rensink himself to keep it going and yet produced persuasive findings worthy of further investigation, findings that could lead to unblocking the human brain’s “forgotten” memories. Unfortunately, all three have since moved on to other projects.

Of course, it’ll take more than one unusually compelling experiment to convince your average God-fearing exorcist priest that a Hasbro-trademarked board game now mass produced in pink isn’t a portal of demonic chaos and darkness.

But was it enough to convince you?

References

- Cheek DB. The meaning of continued hearing sense under general chemo-anesthesia: A progress report and report of a case. The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 1968; 8(4): 275-280.

- Goldacre B. Bad science: Making contact with a helping hand. The Guardian. December 5, 2009. Online. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2009/dec/05/bad-science-ben-goldacre-column

- Patents for Inventions: Abridgments for specifications. Patent Office: Great Britain 1859: 382-383.

- Trippett D. Wagner’s Melodies: Aesthetics and Materialism in German Musical Identity. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. 2013. Print.

- Rodriguez McRobbie L. The Strange and Mysterious History of the Ouija Board. Smithsonian Magazine. October 28, 2013. Online.

- Gauchou H, Rensink R, Fels S. Expression of nonconscious knowledge via ideomotor actions. Consciousness and Cognition 2012; 21(2): 976-982.