Feeding the Belly Brain

You have a second brain. It’s in your gut. Your belly brain has anywhere from 200 million to 500 million neurons* lining your gastrointestinal tract. That’s about as many as in your spinal cord and way more than the 40,000 found in your heart (yep, that’s your third brain). And those gut neurons are in constant communication with your brain. Feed your belly right? You could end up more resilient to stress and your social anxiety might just fade away. But the question is… what should you eat?

On Topic: The Rewire

Wanna Boost Your Memory? Try This

See Also: Green Tea Weight Loss Miracle: Truth or Hype?

It’s not exactly news that the state of your gut has a huge impact on your everyday life. Ask anyone with a chronic digestive problem like Crohn’s disease or irritable bowel syndrome how it’s turned theirs upside down. Hippocrates, the father of western medicine himself, thought 2,400 years ago that “all disease begins in the gut,” giving ancient meaning to the modern cliché “you are what you eat.”

Gut Feeling Is Right

An increasingly hot topic in health circles is the impact of the gut on the mind [1]. Yet it’s not exactly a new subject. In addition to Hippocrates and a slew of physicians who followed him thereafter, Philippe Pinel, the early 19th century founder of French psychiatry, believed the “original seat” of mental illness was in the “epigastric region.” Pinel noticed that key symptoms –constipation, diarrhea, loss of appetite– he paired with a handful of neuroses often involved food, drink and digestion. A melancholic patient refuses to eat. A “maniac” has uncontrollable thirst. In turn, Pinel imposed diets measured down to the centilitre, customized by neurosis and associated symptom, the backbone of patient treatment under his watch at Paris’ infamous Salpêtrière asylum [2].

The field has come a long way since Pinel’s crude diagnostic methods. But the concept that the right diet can heal the psyche while the wrong one may harm it has taken on new meaning in the last decade.

*You know what has 500 million neurons? An octopus. The smartest mollusk on the planet. Think about it. You’ve got as many neurons as an exceptionally astute invertebrate who could outsmart your pet dog operating in your gut.

”To sum up 20 years of neurogastroenterology research, gut neurons need gut bacteria to produce neurochemicals considered critical to wellbeing. Put another way, non-human microorganisms are potentially driving your behavior. And the food you eat, in turn, drives them.”

Alien Invasion

The human gut is overrun by bacteria, microscopic single-celled organisms that outnumber human cells 10 to 1 [3], though recent research challenges that claim [4]. Regardless of who is right, what is clear is there are at least as many bacteria as there are human cells in a given body and, far from representing a hostile takeover, many of these microorganisms are friendly little critters, helping the gastrointestinal tract extract nutrients from food as well as protecting the host body from pathogens, disease-causing bacteria which aren’t so cooperative.

But here’s the stunner.

Above: the humble dopamine molecule. (All photos courtesy of Pixabay)

Your gut’s microbiota is behind the production of 95% of the serotonin in your body [5]. Serotonin. The body’s serenity chemical. Well, one of them anyway. Anti-anxiety and antidepressant drugs like Prozac, Paxil, and Zoloft? Their job is to keep released serotonin circulating for longer periods, increasing the overall amount present in the brain at any given time. More serotonin? More happy. The only problem is we’re not yet sure what serotonin produced in the gut does [6]. Does it also contribute to mood like it does when it circulates in the brain? Gut-produced serotonin can’t pass the blood-brain barrier so it’s a bit of a mystery.

On top of that, as much dopamine is produced in the humble gut as in the brain [7]. Dopamine is a feel-good chemical associated with unexpected rewards. Getting a raise you didn’t see coming? Dopamine isn’t far behind. And the main reason cocaine is one hell of a drug, at least at first, is because it prevents dopamine from being reabsorbed by the neurons that released it in the first place, essentially flooding the system with an amplified rewarding sensation. Does dopamine produce the same effect when it’s generated in the gastrointestinal tract? We don’t really know yet.

And those are just two of the 40 neurochemicals found in the gut.

So to sum up 20 years of neurogastroenterology research, gut neurons need gut bacteria to produce neurochemicals considered critical to wellbeing.

Put another way, non-human microorganisms are potentially driving your behavior. And the food you eat, in turn, drives them.

“All disease begins in the gut.”

HIPPOCRATES

Food: The Gamer-Changer

Your gut microbiome is influenced by a handful of factors, some rather difficult to control like your genetics, your age, and your gender. But stress and diet are also in the game, and they’re yours to manipulate.

The question is… how?

One UCLA study in 2013 [8] featuring 36 healthy female subjects with normal BMIs between the ages of 18 and 53 showed that women showed different fMRI brain scan results after four weeks of ingesting 250ml of fermented milk product daily than before they started the study. For example, there was less activity in the amygdala –the brain’s fear region, its fight-or-flight center– when viewing images of faces showing fear or anger after the 4 weeks of fermented milk product ingestion. Yet women who either drank a non-fermented milk product or nothing at all during the same four-week period showed no change in neurological response to the same stimuli the other women viewed. To quote the researchers, “our data demonstrate that chronic ingestion of a fermented milk product… can modulate the responsiveness of an extensive brain network in healthy women.”

The one question mark with that study is that it was at least partially sponsored by Danone, a company which produces yogurt, so the research was dependent on corporate interests. The study design was sound though. Neither subjects nor experimenters knew who was ingesting the fermented milk product and who was being given a regular milk product which reportedly looked and tasted the same.

A College of William and Mary and University of Maryland study dated 2015 [9] got 710 ethnically diverse college students, both women and men between the ages of 18 and 38 to fill out a series of tests. One was the Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory, a standardized test that reliably detects who might have difficulty with social interaction and performance. Another was the Big Five Personality Inventory, a gold standard in the field of psychology for quickly assessing personality and thus predicting behavior, one I’ve consistently administered myself to research participants and for private sector clients in the past.

Then participants were asked to share the details of their diet and exercise habits.

What researchers discovered was that of the study participants who scored high in neuroticism –the personality trait on the Big Five Personality Inventory that measures anxiety, sense of vulnerability, self-consciousness, lack of moderation, anger, and depression levels– the ones with the lowest scores among those high scorers appeared to eat a diet high in fermented foods, things like miso soup, sauerkraut, dark chocolate, kimchi, tempeh, and in line with other studies, yogurt. Meanwhile, study participants with the highest neuroticism scores of the entire group on average didn’t seem to eat much fermented foods at all.

Meanwhile, it didn’t seem to matter what study participants with low neuroticism scores ate. Those who ate a diet high in fermented foods and those who consumed few fermented foods scored the same on average.

In the end, researchers concluded that fermented foods may have a protective effect on people, in this case young adults, at higher risk of experiencing social anxiety. It’s difficult to come to any solid conclusions though, given the self-reporting nature of the tests (in-person interviews usually provide stronger data). And the conclusion are correlational. Do we know for certain that eating lots of fermented food is what caused those high risk participants to have more manageable anxiety levels? What if people who eat diets high in fermented foods also tend to lead healthier lifestyles and exercise more, activity which has been shown time and time again to reduce anxiety?

Caroline Wallace and Roumen Millev from Queen’s University ostensibly had the same questions [10]. So they conducted a meta-analysis that came out earlier in 2017 comparing the results of ten studies which examined the effects of probiotics (commonly found in fermented food) on depressive symptoms, anxiety, cognitive function. Seven of the ten selected for review were chosen because they were conducted with ideal methodology: subjects were randomly assigned to either experimental or control groups with neither them nor the experimenters aware of who was assigned to what. Wallace and Milley tacked on an extra three studies that weren’t blind like the last seven but which were deemed of sound design nonetheless.

Verdict for depression? Eight out of the ten studies reported improvements in the moods of subjects who ingested probiotics daily. As for stress and anxiety, 8 out ten studies also showed anxiety and stress relief among those who ingested probiotics every day.

And of those 10 studies, 3 looked at cognitive function in one way or another. All three of them claimed daily probiotic intervention improved cognition, with one study showing enhanced problem-solving and reduced self-blame and another greater resilience to cognitive fatigue.

Does that mean everyone should stock up on kimchi and yogurt?

Maybe.

Saying “yes, absolutely, 100%” is still a little premature but one thing is for sure. You don’t need a doctor’s prescription to buy dark chocolate.

- Mayer E. The mind-gut connection: how the hidden conversation within our bodies impacts our mood, our choices, and our overall health. New York: Harper Wave. 2016. Print.

- Pinel P. Traité médico-philosophique sur l’aliénation mentale ou La manie. Paris: Richard, Caille et Ravier. 1801, Print.

- Farmer AD, Randall HA, Aziz Q. It’s a gut feeling: How the gut microbiota affects the state of mind. The Journal of Physiology 2014; 592(14): 2981–88.

- Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS Biology 2016; 14(8): e1002533.

- Sommer F, Backhed F. The gut microbiota–masters of host development and physiology. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2013; 11: 227-38.

- Bornstein JC. Serotonin in the gut: What does it do? Front Neurosci. 2012; 6: 16.

- Eisenhofer G,Aneman A, Friberg P, Hooper D, Fåndriks L, Lonroth H, Hunyady B, Mezey E. Substantial production of dopamine in the human gastrointestinal tract. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 1997; 82(11): 3864-71.

- Tillisch K, Labus J, Kilpatrick L, Jiang Z, Stains J, Ebrat B, Gyonnet D, Legrain-Raspaud S, Trotin B, Naliboff B, Mayer EA. Consumption of fermented milk product with probiotic modulates brain activity. Gastroenterology 2013; 144: 1394-1401.

-

Hilimire MR, DeVylder JE, Forestell CA. Fermented foods, neuroticism, and social anxiety: An interaction model. Psychiatry Research 2015 August; 228(2): 203-8.

-

Wallace CJK, Milev R. The effects of probiotics on depressive symptoms in humans: A systemic review. Annals of General Psychiatry 2017; 16(14).

You have a second brain. It’s in your gut. Your belly brain has anywhere from 200 million to 500 million neurons* lining your gastrointestinal tract. That’s about as many as in your spinal cord and way more than the 40,000 found in your heart (yep, that’s your third brain). And those gut neurons are in constant communication with your brain. Feed your belly right? You could end up more resilient to stress and your social anxiety might just fade away. But the question is… what should you eat?

On Topic: The Rewire

Wanna Boost Your Memory? Try This

See Also: Green Tea Weight Loss Miracle: Truth or Hype?

It’s not exactly news that the state of your gut has a huge impact on your everyday life. Ask anyone with a chronic digestive problem like Crohn’s disease or irritable bowel syndrome how it’s turned theirs upside down. Hippocrates, the father of western medicine himself, thought 2,400 years ago that “all disease begins in the gut,” giving ancient meaning to the modern cliché “you are what you eat.”

Gut Feeling Is Right

An increasingly hot topic in health circles is the impact of the gut on the mind [1]. Yet it’s not exactly a new subject. In addition to Hippocrates and a slew of physicians who followed him thereafter, Philippe Pinel, the early 19th century founder of French psychiatry, believed the “original seat” of mental illness was in the “epigastric region.” Pinel noticed that key symptoms –constipation, diarrhea, loss of appetite– he paired with a handful of neuroses often involved food, drink and digestion. A melancholic patient refuses to eat. A “maniac” has uncontrollable thirst. In turn, Pinel imposed diets measured down to the centilitre, customized by neurosis and associated symptom, the backbone of patient treatment under his watch at Paris’ infamous Salpêtrière asylum [2].

The field has come a long way since Pinel’s crude diagnostic methods. But the concept that the right diet can heal the psyche while the wrong one may harm it has taken on new meaning in the last decade.

*You know what has 500 million neurons? An octopus. The smartest mollusk on the planet. Think about it. You’ve got as many neurons as an exceptionally astute invertebrate who could outsmart your pet dog operating in your gut.

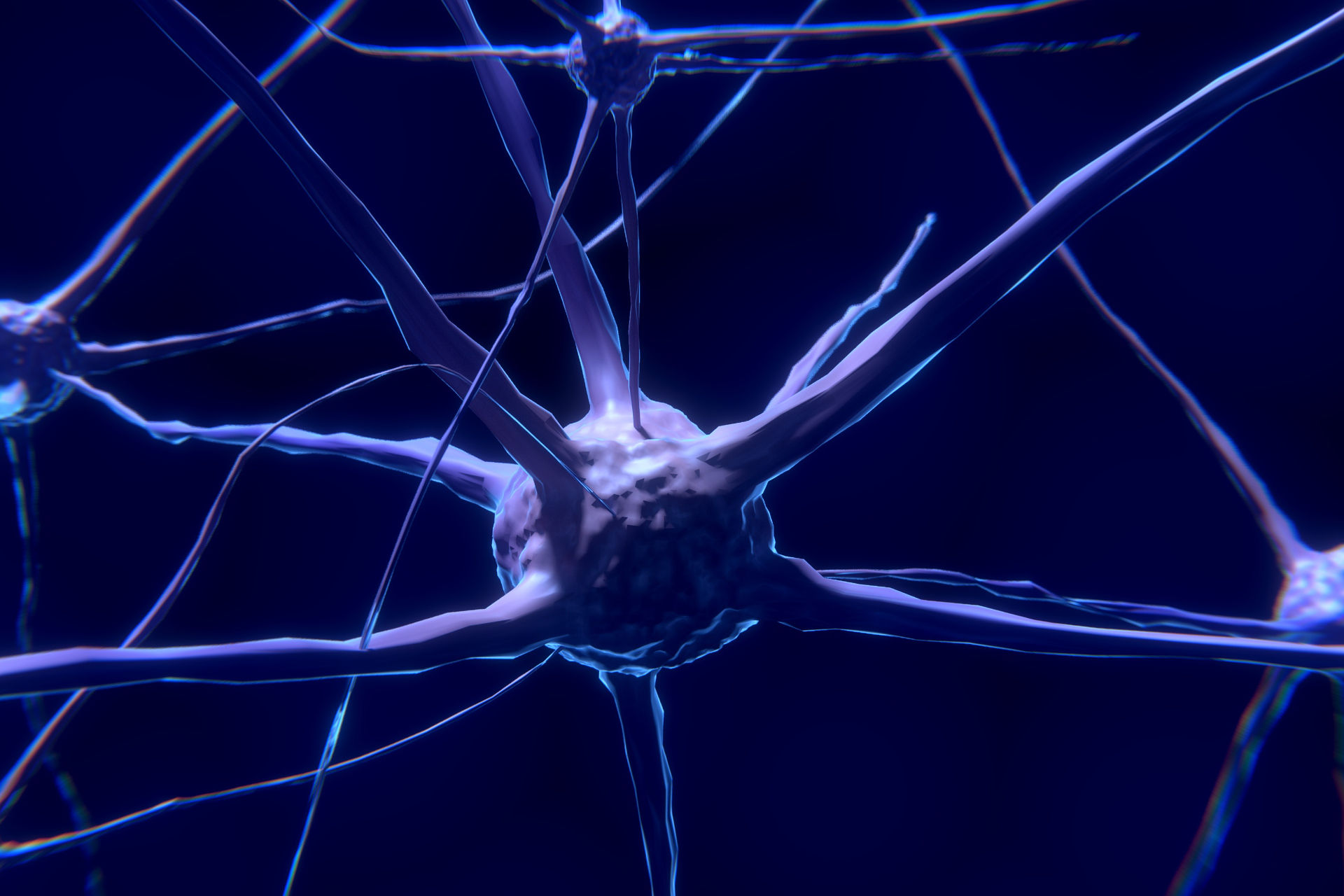

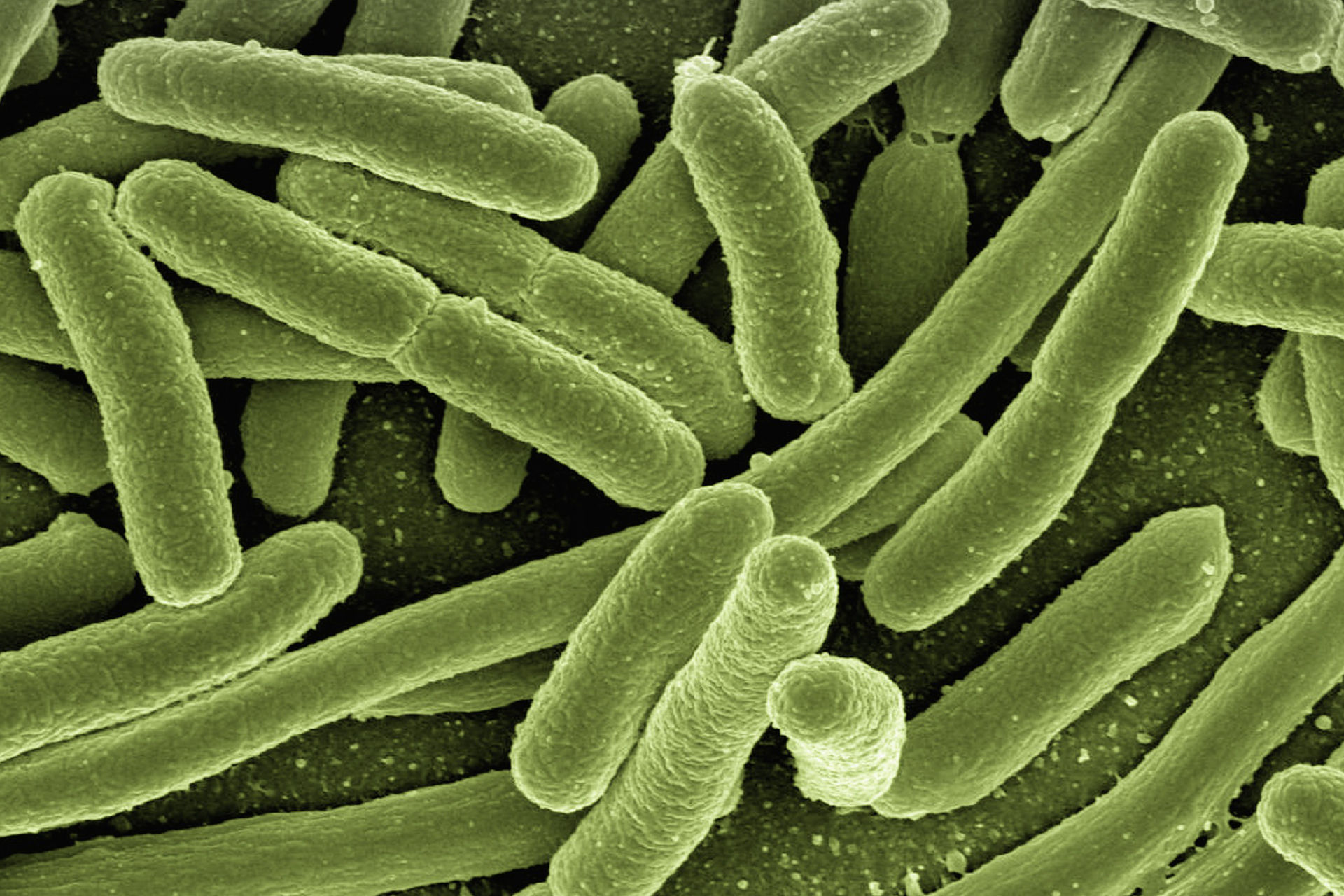

Above: an Escherichia coli bacterium. Contrary to popular belief, most strains of E. coli are harmless. Some are even useful, commonly found strains in human intestines. (Image courtesy of Pixabay)

Alien Invasion

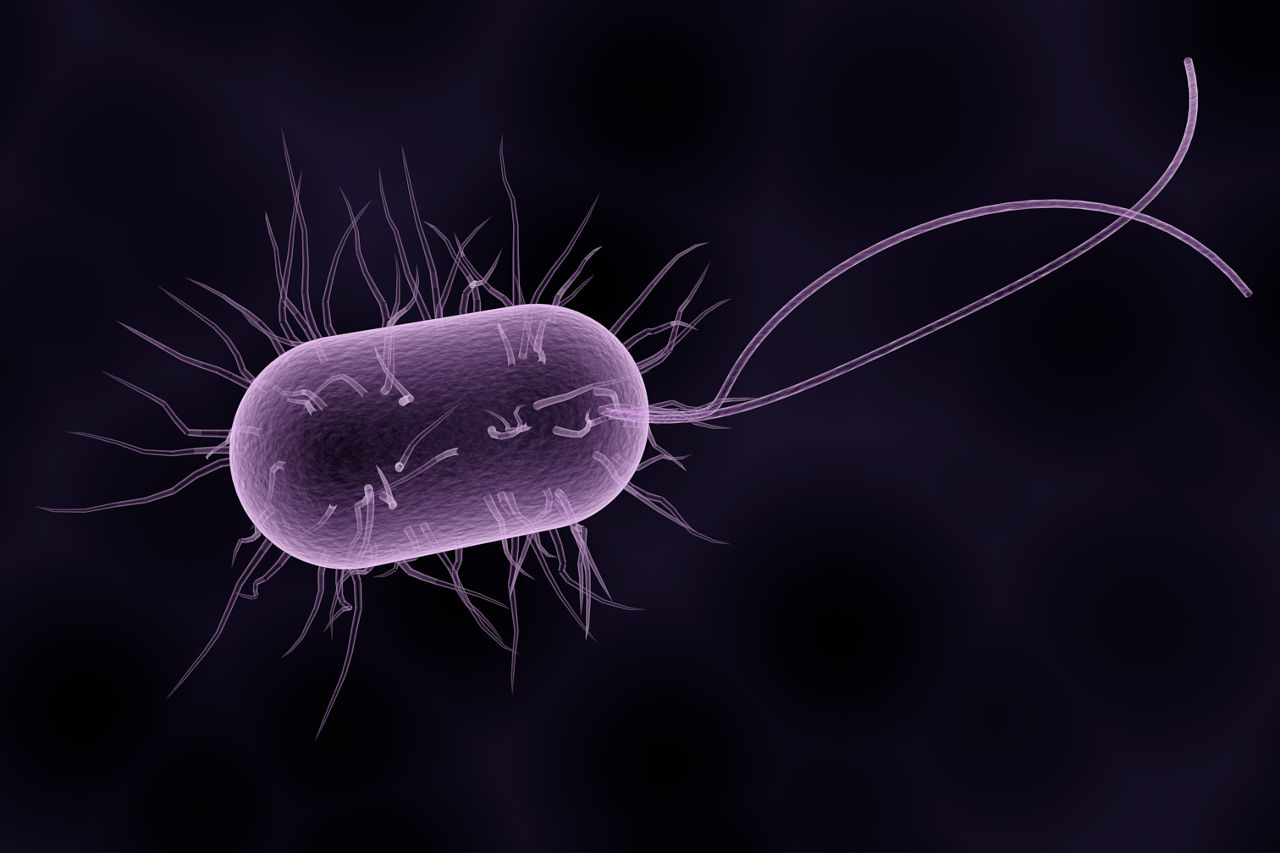

The human gut is overrun by bacteria, microscopic single-celled organisms that outnumber human cells 10 to 1 [3], though recent research challenges that claim [4]. Regardless of who is right, what is clear is there are at least as many bacteria as there are human cells in a given body and, far from representing a hostile takeover, many of these microorganisms are friendly little critters, helping the gastrointestinal tract extract nutrients from food as well as protecting the host body from pathogens, disease-causing bacteria which aren’t so cooperative.

But here’s the stunner.

Your gut’s microbiota is behind the production of 95% of the serotonin in your body [5]. Serotonin. The body’s serenity chemical. Well, one of them anyway. Anti-anxiety and antidepressant drugs like Prozac, Paxil, and Zoloft? Their job is to keep released serotonin circulating for longer periods, increasing the overall amount present in the brain at any given time. More serotonin? More happy. The only problem is we’re not yet sure what serotonin produced in the gut does [6]. Does it also contribute to mood like it does when it circulates in the brain? Gut-produced serotonin can’t pass the blood-brain barrier so it’s a bit of a mystery.

On top of that, as much dopamine is produced in the humble gut as in the brain [7]. Dopamine is a feel-good chemical associated with unexpected rewards. Getting a raise you didn’t see coming? Dopamine isn’t far behind. And the main reason cocaine is one hell of a drug, at least at first, is because it prevents dopamine from being reabsorbed by the neurons that released it in the first place, essentially flooding the system with an amplified rewarding sensation. Does dopamine produce the same effect when it’s generated in the gastrointestinal tract? We don’t really know yet.

And those are just two of the 40 neurochemicals found in the gut.

So to sum up 20 years of neurogastroenterology research, gut neurons need gut bacteria to produce neurochemicals considered critical to a sense of wellbeing.

Put another way, non-human microorganisms are potentially driving your behavior. And the food you eat, in turn, drives them.

(Image courtesy of Pixabay)

”To sum up 20 years of neurogastroenterology research, gut neurons need gut bacteria to produce neurochemicals considered critical to wellbeing. Put another way, non-human microorganisms are potentially driving your behavior. And the food you eat, in turn, drives them.”

Above: kimchi, a fermented food popular in South Korea. (Photo courtesy of Foodiesfeed)

Food: The Gamer-Changer

Your gut microbiome is influenced by a handful of factors, some rather difficult to control like your genetics, your age, and your gender. But stress and diet are also in the game, and they’re yours to manipulate.

The question is… how?

One UCLA study in 2013 [8] featuring 36 healthy female subjects with normal BMIs between the ages of 18 and 53 showed that women showed different fMRI brain scan results after four weeks of ingesting 250ml of fermented milk product daily than before they started the study. For example, there was less activity in the amygdala –the brain’s fear region, its fight-or-flight center– when viewing images of faces showing fear or anger after the 4 weeks of fermented milk product ingestion. Yet women who either drank a non-fermented milk product or nothing at all during the same four-week period showed no change in neurological response to the same stimuli the other women viewed. To quote the researchers, “our data demonstrate that chronic ingestion of a fermented milk product… can modulate the responsiveness of an extensive brain network in healthy women.”

The one question mark with that study is that it was at least partially sponsored by Danone, a company which produces yogurt, so the research was dependent on corporate interests. The study design was sound though. Neither subjects nor experimenters knew who was ingesting the fermented milk product and who was being given a regular milk product which reportedly looked and tasted the same.

A College of William and Mary and University of Maryland study dated 2015 [9] got 710 ethnically diverse college students, both women and men between the ages of 18 and 38 to fill out a series of tests. One was the Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory, a standardized test that reliably detects who might have difficulty with social interaction and performance. Another was the Big Five Personality Inventory, a gold standard in the field of psychology for quickly assessing personality and thus predicting behavior, one I’ve consistently administered myself to research participants and for private sector clients in the past.

Then participants were asked to share the details of their diet and exercise habits.

”All disease begins in the gut.” -Hippocrates (Photo courtesy of Pixabay)

What researchers discovered was that of the study participants who scored high in neuroticism –the personality trait on the Big Five Personality Inventory that measures anxiety, sense of vulnerability, self-consciousness, lack of moderation, anger, and depression levels– the ones with the lowest scores among those high scorers appeared to eat a diet high in fermented foods, things like miso soup, sauerkraut, dark chocolate, kimchi, tempeh, and in line with other studies, yogurt. Meanwhile, study participants with the highest neuroticism scores of the entire group on average didn’t seem to eat much fermented foods at all.

Meanwhile, it didn’t seem to matter what study participants with low neuroticism scores ate. Those who ate a diet high in fermented foods and those who consumed few fermented foods scored the same on average.

In the end, researchers concluded that fermented foods may have a protective effect on people, in this case young adults, at higher risk of experiencing social anxiety. It’s difficult to come to any solid conclusions though, given the self-reporting nature of the tests (in-person interviews usually provide stronger data). And the conclusion are correlational. Do we know for certain that eating lots of fermented food is what caused those high risk participants to have more manageable anxiety levels? What if people who eat diets high in fermented foods also tend to lead healthier lifestyles and exercise more, activity which has been shown time and time again to reduce anxiety?

Caroline Wallace and Roumen Millev from Queen’s University ostensibly had the same questions [10]. So they conducted a meta-analysis that came out earlier in 2017 comparing the results of ten studies which examined the effects of probiotics (commonly found in fermented food) on depressive symptoms, anxiety, cognitive function. Seven of the ten selected for review were chosen because they were conducted with ideal methodology: subjects were randomly assigned to either experimental or control groups with neither them nor the experimenters aware of who was assigned to what. Wallace and Milley tacked on an extra three studies that weren’t blind like the last seven but which were deemed of sound design nonetheless.

Verdict for depression? Eight out of the ten studies reported improvements in the moods of subjects who ingested probiotics daily. As for stress and anxiety, 8 out ten studies also showed anxiety and stress relief among those who ingested probiotics every day.

And of those 10 studies, 3 looked at cognitive function in one way or another. All three of them claimed daily probiotic intervention improved cognition, with one study showing enhanced problem-solving and reduced self-blame and another greater resilience to cognitive fatigue.

Does that mean everyone should stock up on kimchi and yogurt?

Maybe.

Saying “yes, absolutely, 100%” is still a little premature but one thing is for sure. You don’t need a doctor’s prescription to buy dark chocolate.

- Mayer E. The mind-gut connection: how the hidden conversation within our bodies impacts our mood, our choices, and our overall health. New York: Harper Wave. 2016. Print.

- Pinel P. Traité médico-philosophique sur l’aliénation mentale ou La manie. Paris: Richard, Caille et Ravier. 1801, Print.

- Farmer AD, Randall HA, Aziz Q. It’s a gut feeling: How the gut microbiota affects the state of mind. The Journal of Physiology 2014; 592(14): 2981–88.

- Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS Biology 2016; 14(8): e1002533.

- Sommer F, Backhed F. The gut microbiota–masters of host development and physiology. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2013; 11: 227-38.

- Bornstein JC. Serotonin in the gut: What does it do? Front Neurosci. 2012; 6: 16.

- Eisenhofer G,Aneman A, Friberg P, Hooper D, Fåndriks L, Lonroth H, Hunyady B, Mezey E. Substantial production of dopamine in the human gastrointestinal tract. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 1997; 82(11): 3864-71.

- Tillisch K, Labus J, Kilpatrick L, Jiang Z, Stains J, Ebrat B, Gyonnet D, Legrain-Raspaud S, Trotin B, Naliboff B, Mayer EA. Consumption of fermented milk product with probiotic modulates brain activity. Gastroenterology 2013; 144: 1394-1401.

-

Hilimire MR, DeVylder JE, Forestell CA. Fermented foods, neuroticism, and social anxiety: An interaction model. Psychiatry Research 2015 August; 228(2): 203-8.

-

Wallace CJK, Milev R. The effects of probiotics on depressive symptoms in humans: A systemic review. Annals of General Psychiatry 2017; 16(14).