Winter Frost Tea From the Blue Mountains

Tea in India, like in other tea-producing countries, is typically picked in spring, summer, and autumn. But one region in the country waits for a chilly window in January and February when frost hits to pluck its prized leaves, producing a sweetening effect similar to what happens with ice wine grapes.

The Nilgiris, aka the Blue Mountains, are located in the deep south, in the state of Tamul Nadu just beside Kerala. The region is known for its rare winter frost teas made possible by the region’s unique combination of clement temperatures year round and cold winter nights in the higher altitudes where tea estates are located. Leaves are typically plucked the morning after a frosty cold spell, often at elevations higher than that of tea gardens in Darjeeling and Nepal estates. The frost brings out a sweet and rosy flavor, leading to a gentler, mellower tea than your standard Indian black brew.

Leaves are typically plucked the morning after a frosty cold spell, often at elevations higher than that of tea gardens in Darjeeling and Nepal estates. The frost brings out a sweet and rosy flavor, leading to a gentler, mellower tea than your standard Indian black brew.

(All photos in this section taken by Evelyn Reid © all rights reserved, may not be used without photographer’s explicit written permission).

Intrigued, I bought 11 different Nilgiri teas and tasted them over the course of two days. Most were single estate teas as opposed to blends whose origins are often more difficult to trace. Delightful flavors all around, not as delicate as some Darjeeling first flushes and yet not especially in-your-face as with most Assams.

Of them all?

One left me surprised by its clean and uniquely sweet aftertaste, a subtle something that reminded me of roasted almonds, ice cream sugar cones, plums, and maybe even corn bread, the kind of flavor that makes you want to get up and make another cup. And that was sipped straight. No sweetener, lemon, or milk. No other tea from the Nilgiris in that series of 11 had a flavor quite like that.

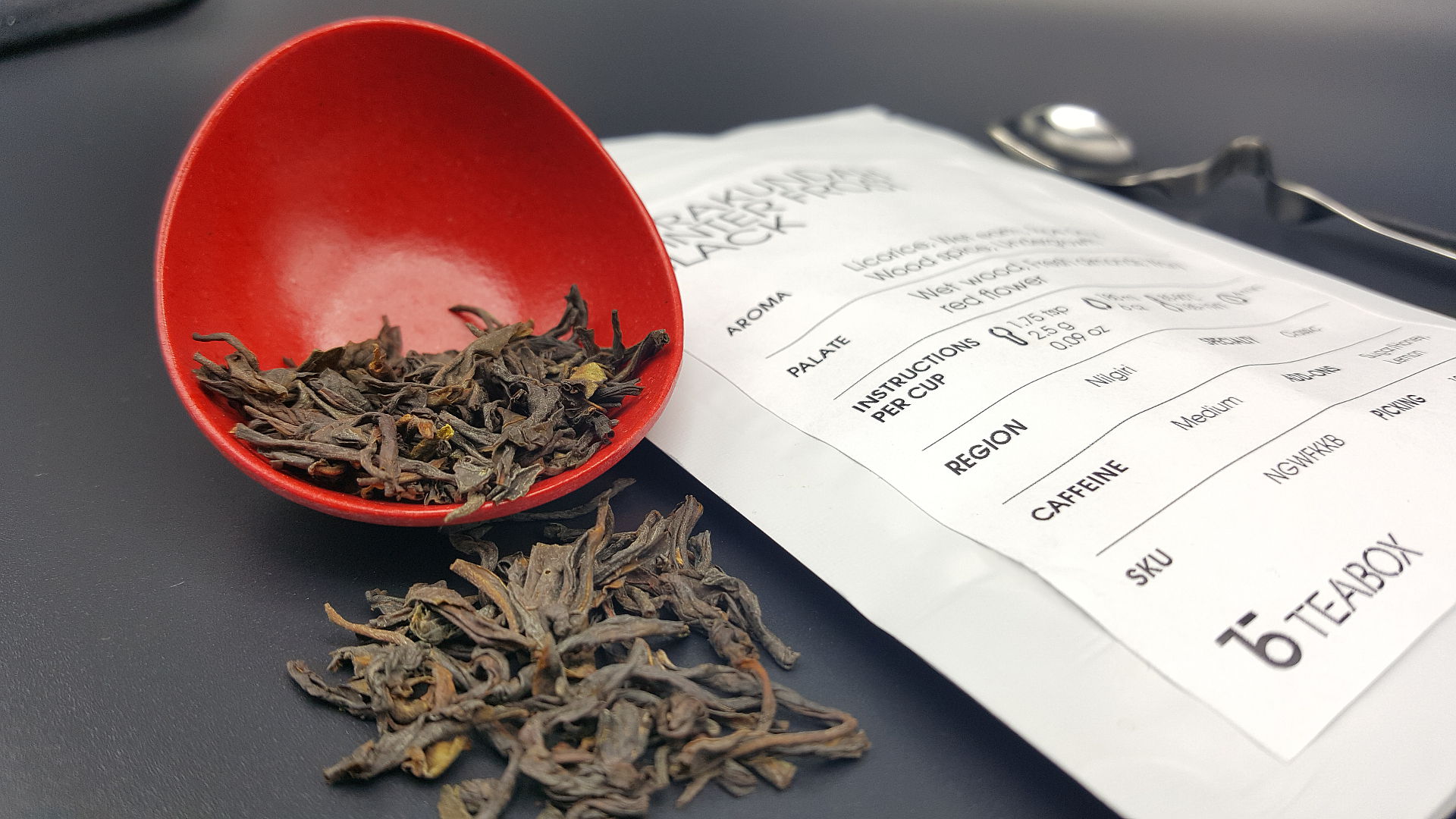

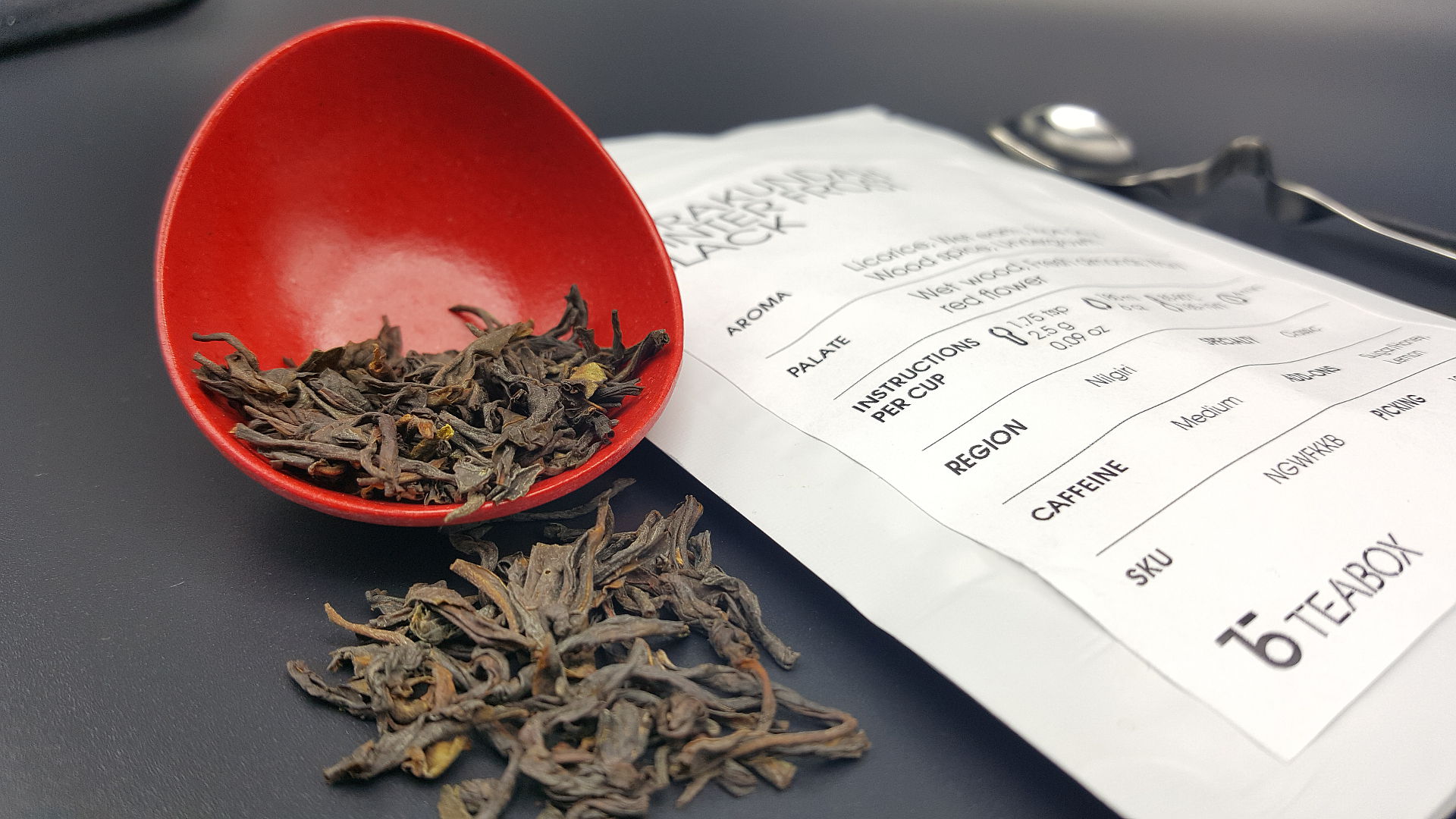

It’s a winter frost black tea produced by Korakundah, a lush and somewhat remote estate sandwiched between two Bengal tiger reserves high in the mountains, the allegedly highest organic tea farm in the world with camellia sinensis plants harvested at close to 8,000 feet above sea level.

Rather than rely on synthetic pesticides, the estate uses eucalyptus oil produced on-site via centuries-old techniques to ward off invasive species. Could that practice in itself contribute to the tea’s distinctive flavor?

Korakundah’s winter frost black tea is not the easiest brew to buy outside of India, unsurprising given the country’s tendency to consume most of its tea products –only 20% of India’s tea yield is exported. I sourced mine through Teabox, a brilliant online company selling a slew of single estate Indian teas which, until they came on the scene, were a pain to find. I’ve bought close to 30 different teas from Teabox since January and the freshness is consistently unreal. I’ll be writing more about their offerings and a few of my favorites in the weeks to come.

…the estate uses eucalyptus oil produced on-site via centuries-old techniques to ward off invasive species. Could that practice in itself contribute to the tea’s distinctive flavor?

(Evelyn Reid © all rights reserved, photo may not be used without photographer’s explicit written permission).

Tea in India, like in other tea-producing countries, is typically picked in spring, summer, and autumn. But one region in the country enjoys a window in January and February when frost hits to pluck its prized leaves, producing a sweetening effect on the leaves similar to what happens with ice wine grapes.

The Nilgiris, aka the Blue Mountains, are located in the deep south, in the state of Tamul Nadu just beside Kerala. The region is known for its rare winter frost teas made possible by the region’s unique combination of clement temperatures year round and cold winter nights in the higher altitudes where tea estates are located. Leaves are typically plucked the morning after a frosty cold spell, often at elevations higher than that of tea gardens in Darjeeling and Nepal estates. The frost brings out a sweet and rosy flavor, leading to a gentler, mellower tea than your standard Indian black brew.

(Evelyn Reid © all rights reserved, photo may not be used without photographer’s explicit written permission).

Intrigued, I bought 11 different Nilgiri teas and tasted them over the course of two days. Most were single estate teas as opposed to blends whose origins are often more difficult to trace. Delightful flavors all around, not as delicate as some Darjeeling first flushes and yet not especially in-your-face as with most Assams.

Of them all?

One left me surprised by its clean and uniquely sweet aftertaste, a subtle something that reminded me of roasted almonds, ice cream sugar cones, plums, and maybe even corn bread, the kind of flavor that makes you want to get up and make another cup. And that was sipped straight. No sweetener, lemon, or milk. No other tea from the Nilgiris in that series of 11 had a flavor quite like that.

(Evelyn Reid © all rights reserved, photo may not be used without photographer’s explicit written permission).

Leaves are typically plucked the morning after a frosty cold spell, often at elevations higher than that of tea gardens in Darjeeling and Nepal estates. The frost brings out a sweet and rosy flavor, leading to a gentler, mellower tea than your standard Indian black brew.

It’s a winter frost black tea produced by Korakundah, a lush and somewhat remote estate sandwiched between two Bengal tiger reserves high in the mountains, the allegedly highest organic tea farm in the world with camellia sinensis plants harvested at close to 8,000 feet above sea level.

Rather than rely on synthetic pesticides, the estate uses eucalyptus oil produced on-site via centuries-old techniques to ward off invasive species. Could that practice in itself contribute to the tea’s distinctive flavor?

Korakundah’s winter frost black tea is not the easiest brew to buy outside of India, unsurprising given the country’s tendency to consume most of its tea products –only 20% of India’s tea yield is exported. I sourced mine through Teabox, a brilliant online company selling a slew of single estate Indian teas which, until they came on the scene, were a pain to find. I’ve bought close to 30 different teas from Teabox since January and the freshness is consistently unreal. I’ll be writing more about their offerings and a few of my favorites in the weeks to come.