Why Tao?

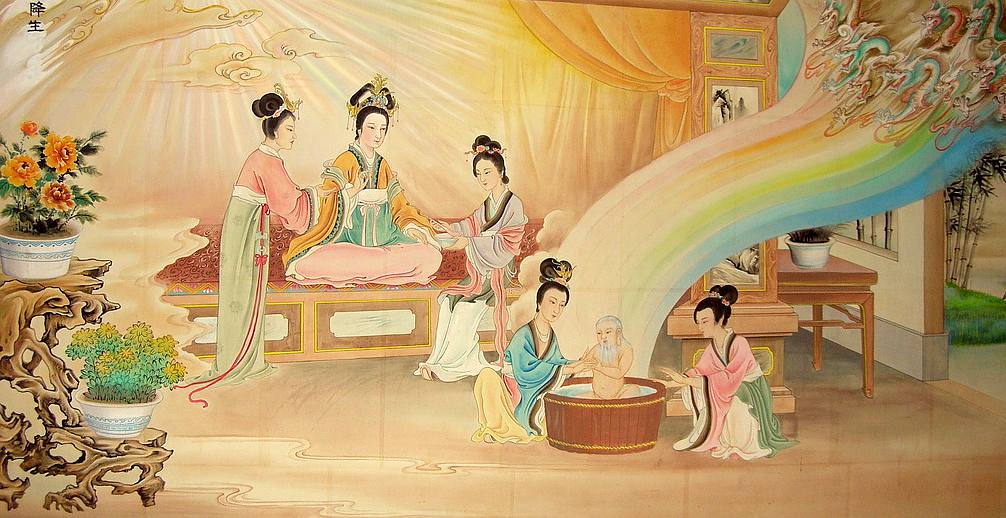

Above: a mural depicting the legend of Lao Tzu’s birth as an “old man” as seen at the Qingyanggong Temple in Chengdu, the largest city in Sichuan, China. It’s based on a hagiography written five hundred years after Lao Tzu’s time circa 100 BCE illustrating how popular legend claims his mother kept him in her womb for 72 years.

There’s no one word that defines Tao. As a Chinese noun, it can mean “way” or “path” or even “principle.” As a verb, it signifies to think, to speak, to suppose.

Yet as a philosophical concept, some say Tao can’t be described in words at all.

All things come from it, the source, the underlying essence of all creation. It’s the culmination of everything. And nothing. Tao existed before you and it will endure after you. And it is always around you. But you can’t see it, smell it, hear it, nor taste it, much less hold it in your hand.

It simply is.

According to Tao Te Ching—“The Book of the Way and Its Virtue,” just one of the many possible translations of the title—following “the path” leads to a life of harmony:

“She who is centered in the Tao

can go where she wishes, without danger.

She perceives the universal harmony,

even amid great pain,

because she has found peace in her heart.”

–Tao Te Ching, Chapter 35, translated by Stephen Mitchell

Tao Te Ching is the first text in recorded history on the subject of Tao. It’s attributed to a sage named Lao Tzu who lived anywhere from 2,300 to over 2,500 years ago. However, select historians think the book is not the doing of one man but rather an amalgamation of texts from different authors with wisdom possibly predating its publication another 2,000 years, a philosophy that possibly formed around the same time as Ancient Egypt’s first dynasty and Ancient India’s Vedic age.

Today, Tao Te Ching is the second most translated book in the world. And it’s both baffled and inspired readers for generations. And that’s in reference to the original Chinese version. Different English translations of it appear to be saying different things when comparing the verses, relaying alternate yet sometimes similar messages, an inherent byproduct of attempting to translate a rich and complex written language like Chinese.

And it’s taken over two millennia but science appears to finally be catching up with “the Way” as described by the enigmatic and charismatic Chuang Tzu, a Chinese philosopher from the 4th century BCE believed to be the author—according to scholars, one of the authors—behind the eponymous Chuang Tzu, a text which Taoist scholar and practitioner Chad Hansen claims is, at its essence, “a book of strategies of how to get into a state of “wu wei” or flow, a state of effortlessness in your mind.”

Hanson also suggests that Chuang Tzu’s philosophy, while extremely similar to that of Lao Tzu’s, is more easily applied in a modern, urban world. Whereas Lao Tzu believed that we should physically leave society and return to nature in order to live in accordance with Tao, Chuang Tzu believed that we could be in the world, but not of it.

As per Hanson, “all we have to do is refrain from what drives society.” Greed, lust, violence, and fame-seeking spring to mind.

Tao is the source, the underlying essence of all creation. But you can’t see it, smell it, hear it, nor taste it, much less hold it in your hand. It simply is.

However, Chuang Tzu was no chaste hermit ascetic alone in a cave or on a mountaintop. In many ways, he lived a normal, everyday life. Chapter 18 of Chuang Tzu, for example, mentions he was married with children. What can be gathered from his interpretation of Tao is that one does not embody “the way” by simply refraining from life’s pleasures. What Chuang Tzu is saying is that which he and other sages claim “drives society” is not actually beneficial to us, as much as we might believe it is. Consequently, Chuang Tzu’s philosophy is about navigating these urges in a way—“the way”—that leads one to consistently experience a state of harmony. Some people might even interpret that as happiness.

Incidentally, I carried a copy of The Way of Chuang Tzu* on me everywhere I went starting in 2008 and for the better part of four years. Four years of never leaving the house without its compact chapters jammed into my bag alongside a pocket-sized paperback of The Little Prince. To say Chuang Tzu’s stories and insights brought me comfort in a time of personal despair is an understatement.

And it occurred to me as I read and reread key passages that there was something palpably modern about the ancient text. I could see reflections of my psychology studies and research-based developments in its pages.

Hence Where’s Your Head‘s Tao du Jour, an opportunity to ponder “the path” which may, either directly or less so, embody what I dub “the what of happy.” Some days contemplate the wisdom of the ancients. On others, Tao du Jour considers more modern insights infused with the spirit of Tao. And yet other Tao du Jour entries may contain no words at all, simple pictures or illustrations that evoke the essence of that which, if you ask its sages, has no name.

*It was the Thomas Merton translation, which bears mention considering how different various Chuang Tzu translations are from each other in general. Makes for an even more fascinating read as you discover new perspectives and insights from one interpretation to the next.

by Evelyn Reid

Above: a mural depicting the legend of Lao Tzu’s birth as an “old man” as seen at the Qingyanggong Temple in Chengdu, the largest city in Sichuan, China. It’s based on a hagiography written five hundred years after Lao Tzu’s time circa 100 BCE illustrating how popular legend claims his mother kept him in her womb for 72 years.

There’s no one word that defines Tao. As a Chinese noun, it can mean “way” or “path” or even “principle.” As a verb, it signifies to think, to speak, to suppose.

Yet as a philosophical concept, some say Tao can’t be described in words at all.

All things come from it, the source, the underlying essence of all creation. It’s the culmination of everything. And nothing. Tao existed before you and it will endure after you. And it is always around you. But you can’t see it, smell it, hear it, nor taste it, much less hold it in your hand.

It simply is.

According to Tao Te Ching—“The Book of the Way and Its Virtue,” just one of the many possible translations of the title—following “the path” leads to a life of harmony:

Lao Tzu (aka Laozi) riding an ox (or water buffalo) as he leaves China for the West

“She who is centered in the Tao

can go where she wishes, without danger.

She perceives the universal harmony,

even amid great pain,

because she has found peace in her heart.”

Tao Te Ching, Chapter 35, translated by Stephen Mitchell

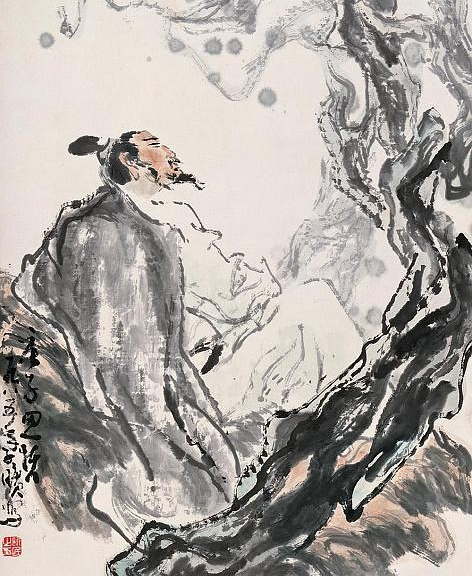

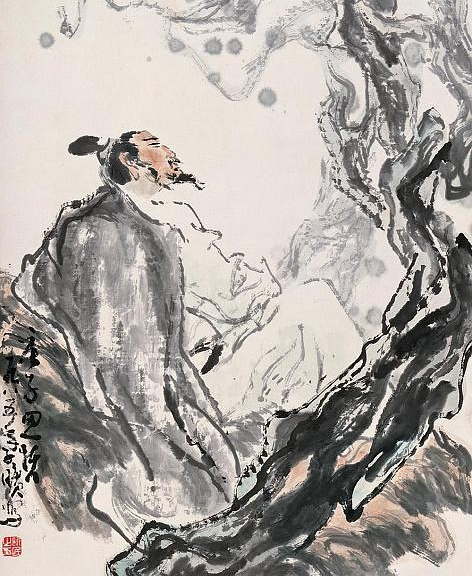

An artistic interpretation of Chuang Tzu in nature.

Tao Te Ching is the first text in recorded history on the subject of Tao. It’s attributed to a sage named Lao Tzu who lived anywhere from 2,300 to over 2,500 years ago. However, select historians think the book is not the doing of one man but rather an amalgamation of texts from different authors with wisdom possibly predating its publication another 2,000 years, a philosophy which possibly formed around the same time as Ancient Egypt’s first dynasty and Ancient India’s Vedic age.

Today, Tao Te Ching is the second most translated book in the world. And it’s both baffled and inspired readers for generations. And that’s in reference to the original Chinese version. Different English translations of it appear to be saying different things when comparing the verses, relaying alternate yet sometimes similar messages, an inherent byproduct of attempting to translate a rich and complex written language like Chinese.

A classic rendition of Chuang Tzu (aka Zhuangzi) sleeping.

And it’s taken over two millennia but science appears to finally be catching up with “the Way” as described by the enigmatic and charismatic Chuang Tzu, a Chinese philosopher from the 4th century BCE believed to be the author—according to scholars, one of the authors—of the eponymous Chuang Tzu, a text which Taoist scholar and practitioner Chad Hansen claims is, at its essence, “a book of strategies of how to get into a state of “wu wei” or flow, a state of effortlessness in your mind.”

Hanson also suggests that Chuang Tzu’s philosophy, while extremely similar to that of Lao Tzu’s, is more easily applied in a modern, urban world. Whereas Lao Tzu believed that we should physically leave society and return to nature in order to live in accordance with Tao, Chuang Tzu believed that we could be in the world, but not of it.

As per Hanson, “all we have to do is refrain from what drives society.” Greed, lust, violence, and fame-seeking spring to mind.

Tao is the source, the underlying essence of all creation. But you can’t see it, smell it, hear it, nor taste it, much less hold it in your hand. It simply is.

However, Chuang Tzu was no chaste hermit ascetic alone in a cave or on a mountaintop. In many ways, he lived a normal, everyday life. Chapter 18 of Chuang Tzu, for example, mentions he was married with children. What can be gathered from his interpretation of Tao is that one does not embody “the way” by simply refraining from life’s pleasures. What Chuang Tzu is saying is that which he and other sages claim “drives society” is not actually beneficial to us, as much as we might believe it is. Consequently, Chuang Tzu’s philosophy is about navigating these urges in a way—“the way”—that leads one to consistently experience a state of harmony. Some people might even interpret that as happiness.

Winnie the Pooh, an exceedingly cuddly bear, lover of honey, and Tao’s best-known representative in the West courtesy of The Tao of Pooh, a 1983 book which spent 49 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list. Its author, Benjamin Hoff, suggests in so many words that Pooh Bear’s personality and way of being embody the essence of Tao.

Incidentally, I carried a copy of The Way of Chuang Tzu* on me everywhere I went starting in 2008 and for the better part of four years, four years of never leaving the house without its compact chapters jammed into my bag alongside a pocket-sized paperback of The Little Prince. To say Chuang Tzu’s stories and insights brought me comfort in a time of personal despair is an understatement.

And it occurred to me as I read and reread key passages that there was something palpably modern about the ancient text. I could see reflections of my psychology studies and research-based developments in its pages.

Hence Where’s Your Head‘s Tao du Jour, an opportunity to ponder “the path” which may, either directly or less so, embody what I dub “the what of happy.” Some days contemplate the wisdom of the ancients. On others, Tao du Jour considers more modern insights infused with the spirit of Tao. And yet other Tao du Jour entries may contain no words at all, simple pictures or illustrations that evoke the essence of that which, if you ask its sages, has no name.

*It was the Thomas Merton translation, which bears mention considering how different various Chuang Tzu translations are from each other in general. Makes for an even more fascinating read as you discover new perspectives and insights from one interpretation to the next.